ECScape: Hijacking IAM Privileges in Amazon ECS

This post is Part 2 of a series on Amazon ECS security. In Part 1 - Under the Hood of Amazon ECS on EC2, we explored how the ECS agent, IAM roles, and the ECS control plane (ACS) work together to provide credentials to tasks. In this Part 2, we focus on a critical vulnerability that exploits those mechanisms to hijack IAM privileges across ECS tasks.

Cloud environments offer unparalleled flexibility and scalability, but they also introduce complex security considerations. In Amazon Web Services (AWS), subtle interactions between services can lead to unexpected vulnerabilities. In this post, I’ll share how I discovered a critical cross-container IAM credential theft vulnerability in Amazon ECS (Elastic Container Service) – a flaw that breaks the assumed IAM role isolation between ECS tasks. This is the story of ECScape, an exploit that hijacks IAM privileges across co-located containers, how we pulled it off, and what it means for cloud container security.

Resources

TL;DR

Vulnerability Discovered: I found a way to abuse an undocumented ECS internal protocol to grab AWS credentials belonging to other ECS tasks on the same EC2 instance. A malicious container with a low-privileged IAM role can hijack the permissions of a higher-privileged container running on the same host.

Real-World Impact: In practice, this means a compromised app in your ECS cluster could escalate to admin privileges by stealing credentials from a more privileged task. This undermines IAM role isolation – one container can effectively become any other on the same host in terms of AWS access.

How It Works: Amazon ECS tasks retrieve credentials via a local metadata service (169.254.170.2) with a unique credentials endpoint for each task. We discovered that by exploiting how ECS identifies tasks in this process, an attacker can masquerade as the ECS agent and obtain credentials for any task on the host. No container breakout (no host root access) was required – just clever network and system trickery from within the container’s own namespace.

Stealth Factor: The stolen keys work exactly like the real task’s keys. AWS CloudTrail will attribute API calls to the victim task’s role, so initial detection is tough – it appears as if the victim task is performing the actions.

Mitigations: If you run ECS on EC2, avoid deploying high-privilege tasks alongside untrusted or low-privilege tasks on the same instance. Consider dedicated hosts or node isolation for critical services, or use AWS Fargate (each task in its own microVM) for true separation. Disable or restrict IMDS access for tasks wherever possible (block 169.254.169.254, enforce IMDSv2, or use the ECS ECS_AWSVPC_BLOCK_IMDS setting). Also enforce least privilege on all task IAM roles and drop unneeded Linux capabilities (to limit what a compromised container can do). We’ll cover best practices and detection hints later in this post.

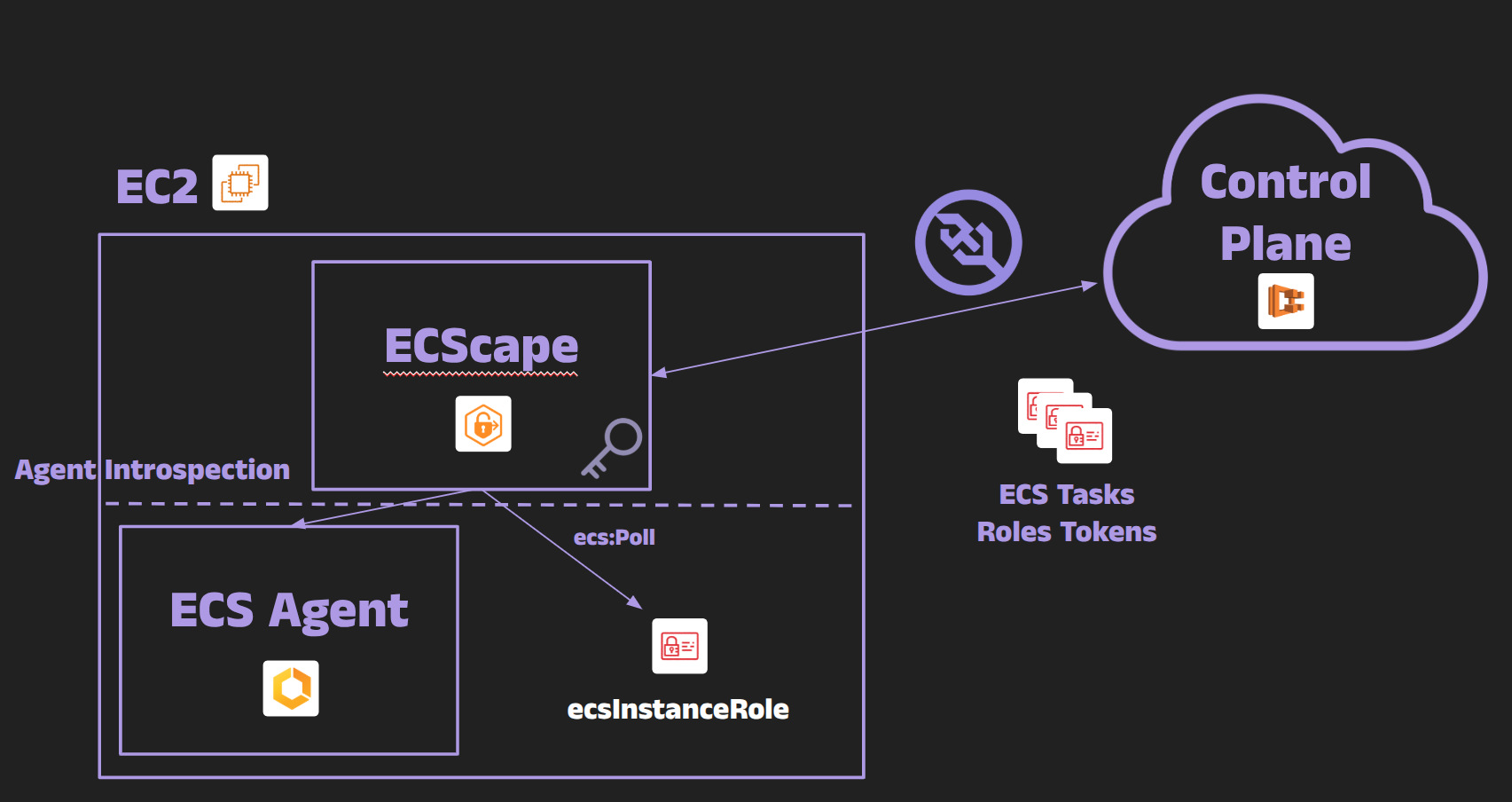

Quick refresher: on EC2 launch type, the ECS control plane assumes each task role, pushes those credentials over the ACS WebSocket to the agent, and the agent serves them to tasks via 169.254.170.2. ECScape abuses that delivery path.

Discovery

I didn’t set out to break ECS; my original goal was to finish an eBPF-based monitoring tool that could watch ECS workloads in real time. To build accurate per-task dashboards, I needed a quick, local way to map processes → containers → ECS tasks and then tag them with cluster name, task ARN, and service name.

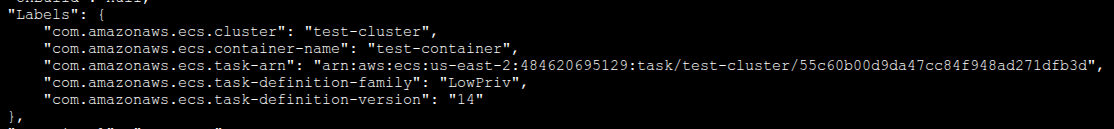

While experimenting, I first tried to scrape the Docker container labels that ECS automatically adds to each task. Those labels include the task ARN, task definition family (with revision), cluster ARN, and container name – but the service name is conspicuously absent.

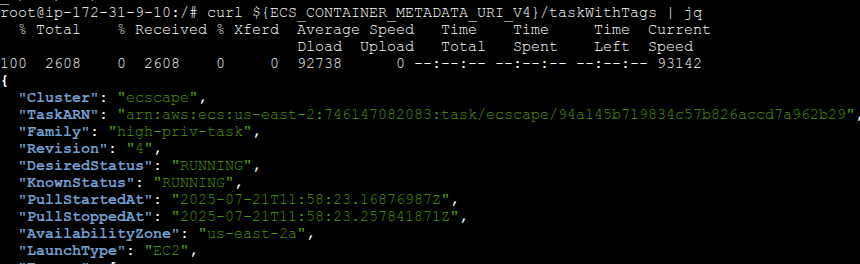

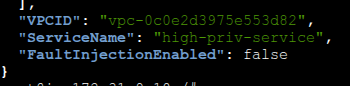

To get the missing service name, I turned to the ECS Task Metadata endpoint (version 4) that the ECS agent exposes inside each container’s network namespace (at 169.254.170.2/v4/…). Querying that endpoint from within a container returned all the details I needed, including the service name, task definition family, revision, and more. Perfect for my monitoring use case.

Naturally, I wondered if my eBPF-based sensor could simply mimic what the agent does - query the same metadata endpoint and stitch the data together for any process on the host. Before trying that, I double-checked the IAM permissions of the EC2 instance’s IAM role (the ecsInstanceRole attached to the container host) and noticed something odd: it did not have ECS APIs like ecs:ListServices or anything that would normally reveal a service name. Yet the agent clearly knew the service name for each task - it was able to hand it to me via the metadata endpoint. So the agent was clearly getting it from the ECS control plane, not via public ECS APIs.

Curiosity led me down a rabbit hole of packet capture. I set up a small local proxy to watch the traffic between the ECS agent and AWS endpoints. What I observed was startling:

The ECS agent established a WebSocket connection to an AWS endpoint – what I later learned is the ECS Agent Communication Service (ACS), the control-plane channel for agents.

In the WebSocket handshake request, a query parameter stood out: ?sendCredentials=true.

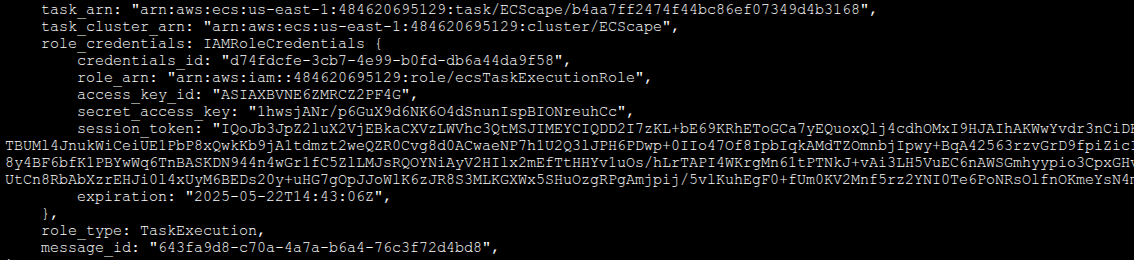

Shortly after the connection was established, the agent’s WebSocket started receiving cleartext JSON blobs that looked very much like IAM credential payloads for tasks. They contained Access Key IDs, Secret Keys, and Session Tokens – the credentials that the agent would later serve to the respective containers.

At this moment, I realized that the ECS control plane was actively pushing task credentials down to the agent over this WebSocket channel. Normally, this is fine - it’s how the agent gets credentials to give to each task’s container - but it got me thinking: if I could somehow tap into that channel, I might capture credentials that weren’t meant for my container. My thought was: if the control plane hands out all task credentials to the agent, could I pose as the agent and trick AWS into sending me those credentials?

That question was the genesis of ECScape - an attack that is essentially about escaping the container’s confines and impersonating the ECS agent to access everything.

The ECScape Exploit: Impersonating the ECS Agent to Steal All Credentials

Now we’ll walk through how ECScape actually works in practice, step by step. The goal for the attacker (a malicious process in one container) is to obtain the IAM credentials of all other tasks on the same EC2 host. To do this, the attacker will:

Obtain the host’s IAM role credentials (so it can act as the ECS agent).

Discover the ECS control plane endpoint that the agent talks to.

Gather the necessary identifiers (cluster name/ARN, container instance ARN, etc.) to authenticate as the agent.

Establish a fake agent session (WebSocket) with the ECS control plane and request sendCredentials.

Harvest credentials for all running tasks on that instance, then use them for further exploitation.

Let’s break these down in detail:

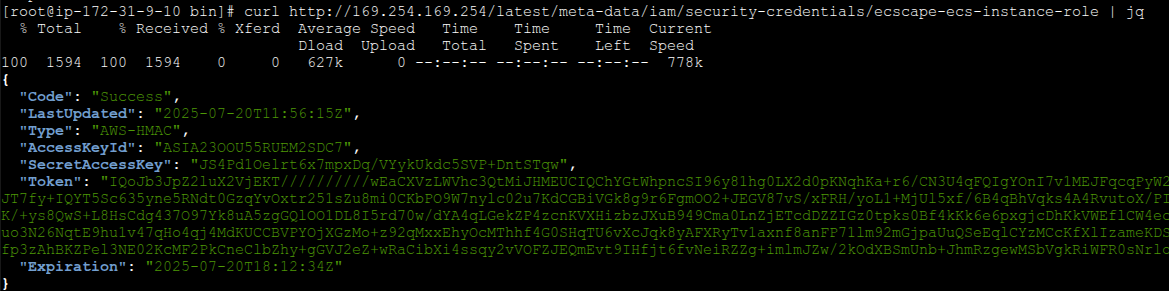

Step 1: Steal EC2 Instance Role Credentials via IMDS

The attacker’s starting point is a compromised container (any low-privileged ECS task running on EC2). By default, unless prevented, containers can query the instance metadata service (IMDS). A simple curl request to http://169.254.169.254/latest/meta-data/iam/security-credentials/{InstanceProfileName} will return the Access Key, Secret Key, and Session Token for the EC2 host’s IAM role. These are the same credentials that the ECS agent on the host uses for its API calls. Now our malicious container has obtained the host instance role credentials.

At this point, the attacker possesses the EC2 instance’s temporary credentials (an STS session representing the container instance). Importantly, these are not the task role credentials of any application container; having the instance profile’s credentials alone doesn’t automatically let you assume the roles of tasks because of IAM trust boundaries:

Typical ECS task roles trust only the service principal ecs-tasks.amazonaws.com (the ECS service), not the EC2 instance role itself.

The instance profile’s policy also usually lacks sts:AssumeRole permissions on task role ARNs.

Because of these restrictions, if the attacker tried to directly call AWS STS to assume another task’s role using the instance credentials, it would fail due to the task role’s trust policy (and likely missing IAM permissions). In other words, the attacker can’t simply pivot to task roles by normal AssumeRole API calls. They need another way – which is where impersonating the agent comes in.

Security note: Reading IMDS from within the container (an HTTP GET) is not logged by CloudTrail, so this initial credential theft is stealthy. If the attacker uses the stolen instance credentials to call AWS APIs (as they will in subsequent steps), those actions will appear in CloudTrail logs as if performed by the instance role.

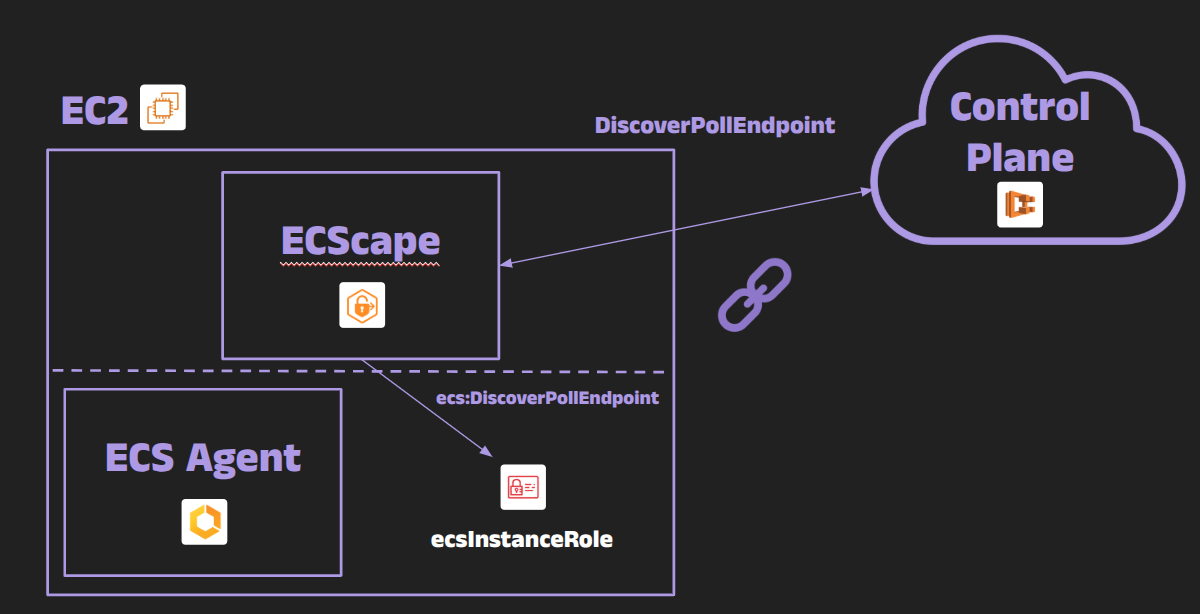

Step 2: Discover the Poll Endpoint URL (ecs:DiscoverPollEndpoint)

The ECS agent doesn’t talk to the control plane at a generic public API endpoint. Instead, AWS provides a specific polling endpoint for each cluster and container instance. Using the stolen instance role credentials, the attacker calls the ECS API ecs:DiscoverPollEndpoint. This API returns a URL, something like https://ecs-a-1..amazonaws.com, which is the endpoint the agent should connect to in order to receive ACS messages.

The instance IAM role is allowed to call DiscoverPollEndpoint (it’s required for the agent to function). If for some reason this API call failed, the endpoint might be guessable (it tends to include the region and some cluster-specific identifier), but typically using the API is straightforward and succeeds with default permissions. Now the attacker knows where to initiate the connection for the control plane communications.

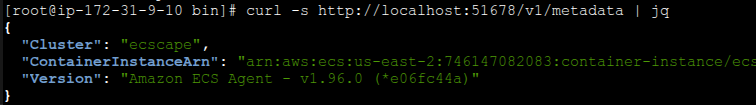

Step 3: Gather Required Identifiers (Cluster, Container Instance ARN, etc.)

When the real ECS agent connects to ACS, it includes various identifiers so the backend knows which cluster and which specific container instance (EC2 host) is checking in. To convincingly masquerade as the agent, the attacker needs to supply these identifiers. Important values include:

Cluster ARN – identifies the ECS cluster.

Container Instance ARN – the unique ARN assigned to the EC2 instance within the cluster (essentially the “agent’s identity” in the cluster).

Agent version info – a client version string.

Docker version – the Docker runtime version on the host.

ACS protocol version – the protocol version for ACS messages.

Sequence number – an initial sequence number for message ordering.

How can the attacker get these? The Task Metadata endpoint we used earlier (169.254.170.2) can provide the Cluster ARN easily (since each task’s metadata includes the cluster). The tricky one is the Container Instance ARN, which isn’t exposed to tasks via the normal metadata endpoint. However, ECS has an introspection API on the agent (normally accessed from the host) that can return the container instance ARN and other info. In my exploit, I found that by querying a specific local endpoint, I could retrieve the container instance ARN from inside the container. In some cases, one could also call ecs:ListContainerInstances via AWS APIs to get it, but that might require additional IAM permissions that the instance role doesn’t have by default. I leveraged the agent’s introspection API to get everything I needed – it returned the container instance ARN and even the agent’s software version.

Note: The fact that a container can access the agent’s introspection API is itself a minor isolation gap. Typically, that API might be bound to localhost or a Unix socket on the host. If it’s exposed on a link-local address and iptables rules don’t filter it out, a container could reach it. Small piece of the chain, but shows how one exposure can help an attacker.

Armed with the cluster ARN, container instance ARN, and other identifiers, the attacker is ready to masquerade as the ECS agent.

Step 4: Forge and Sign the ACS WebSocket Request (Impersonating the Agent)

Now the attacker has to initiate a fake agent session with the ECS control plane. Using the Poll endpoint URL from Step 2 (e.g. something like https://ecs-a-1.region.amazonaws.com) and the identifiers from Step 3, the attacker constructs a WebSocket connection request that looks just like the one the real ECS agent would send. Crucially, this request must be SigV4-signed using the stolen instance profile credentials, so that AWS will authenticate it as coming from the legitimate container instance (the same signing process the real agent uses for API calls).

The WebSocket URL includes query parameters for all those identifiers and settings, for example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

wss://ecs-a-1.<region>.amazonaws.com/ws?

agentHash=<agent-hash>&

agentVersion=<agent-version>&

clusterArn=arn:aws:ecs:<region>:<account-id>:cluster/<cluster-name>&

containerInstanceArn=arn:aws:ecs:<region>:<account-id>:container-instance/<instance-uuid>&

dockerVersion=<docker-version>&

protocolVersion=<protocol-version>&

seqNum=1&

sendCredentials=true

A few important notes on this step:

The request is signed with AWS Signature Version 4 using the instance role’s Access Key, Secret, and Token we stole in Step 1. The instance role’s IAM policy must allow at least the ecs:Poll action (and typically also ecs:DiscoverPollEndpoint which we used). The default ECS instance role policy does include ecs:Poll, so we’re good. If ecs:Poll were not permitted, the control plane would reject the connection. Removing ecs:Poll would also break the real agent’s auth, so it’s not an option.

We include the parameter sendCredentials=true in the query string. This is the magic flag that tells the ACS backend “this agent is interested in receiving IAM credential payloads for all tasks on this instance.” (The normal agent always sets this as well, since it needs the credentials.)

The connection upgrade to WebSocket is treated like an HTTPS request under the hood, so all the usual signed headers (AWS date, authorization, etc.) are included. Once the handshake completes, it becomes a persistent WebSocket.

If our signing and parameters are all correct, AWS will accept the WebSocket connection as if it were the real ECS agent on that container instance. From the perspective of the ECS control plane, our malicious process is now just another authorized agent session for that instance.

It turned out that AWS did not strictly enforce a one-agent-per-instance rule at the time. In my tests, I ended up with two concurrent connections for the same container instance – one from the real ECS agent, and one from my impersonating session. The control plane happily sent messages to both. (If AWS had limited it to one connection at a time, my fake agent session might have knocked the real agent offline or been refused, which could have raised flags. But as it stood, I could stay completely under the radar while eavesdropping on the stream.)

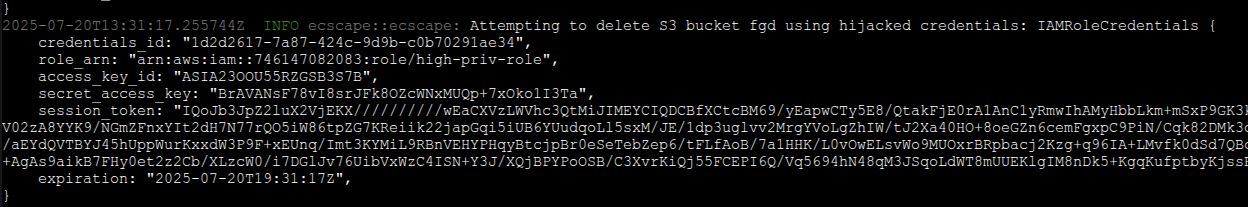

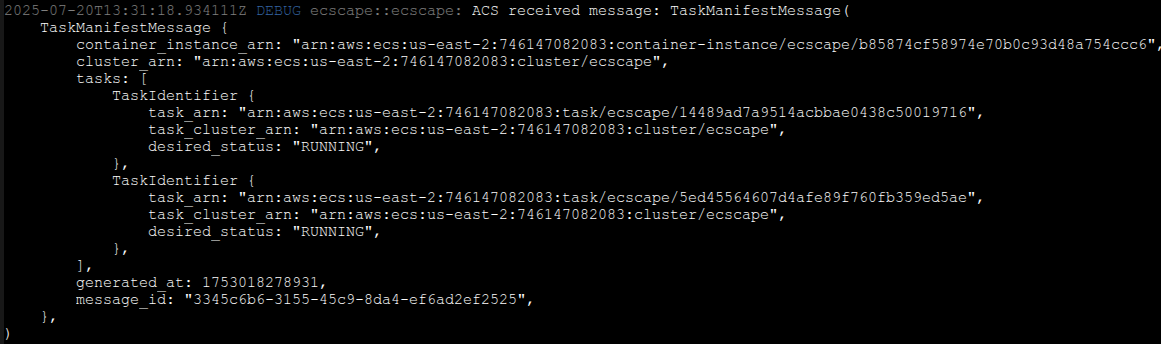

Step 5: Harvest All Task Role Credentials from ACS

With the forged WebSocket session open, the attacker is now riding the same multiplexed ACS message stream as the real ECS agent. Over this channel, the ECS control plane continuously pushes structured messages: heartbeats (keep-alives with sequence numbers), task lifecycle directives (start/stop/update commands), telemetry data, and – most importantly – IamRoleCredentials payloads.

It’s important to clarify how ECS normally handles task credentials: the ECS service (principal ecs-tasks.amazonaws.com in AWS) performs the STS:AssumeRole for each task’s role (and the task execution role, if one is used). The ECS agent never calls STS itself. Instead, the control plane assumes the role on your behalf, obtains a set of temporary credentials, and then delivers those credentials down to the agent via ACS. The agent caches them in memory and serves them to the container when the container asks for its credentials. (Execution role credentials are similarly delivered but used internally by the agent for pulling images, writing logs, etc., and are not exposed through the metadata endpoint.)

Because our forged agent session included sendCredentials=true and authenticated as the correct container instance, the ECS control plane proceeds to push an IamRoleCredentials message for every currently running task on that instance that has an IAM role. Each credentials message includes the task’s ARN (so you know which task it belongs to), the IAM role ARN, a credentials ID (used in the metadata URI), the AccessKeyId, SecretAccessKey, SessionToken, an expiration time, and a flag for the role type (whether it’s the task’s application role or the task’s execution role). If there are, say, five tasks with IAM roles running on that host, as soon as we connect we’ll receive five distinct credential sets. One of those will be for our own compromised task (which we already have and don’t need), but the others belong to other tasks – representing immediate lateral escalation opportunities.

The forged agent channel also remains stealthy. Our malicious session mimics the agent’s expected behavior – acknowledging messages, incrementing sequence numbers, sending heartbeats – so nothing seems amiss. ECS actually allows concurrent authenticated sessions for the same container instance, so the real agent continues to operate normally and also receives the same credential messages. From the control plane’s point of view, there’s no anomaly; it’s just delivering credentials and updates to an agent session as usual.

CloudTrail visibility: The AWS API calls we made to set up this exploit (e.g. the ecs:DiscoverPollEndpoint call, and the long-poll ecs:Poll connection which underlies the WebSocket) will show up in CloudTrail as actions by the container instance’s IAM role. Any subsequent AWS actions we perform with stolen task credentials will show up as those task roles performing the actions (with the task’s ARN in the session context). That is one of the few potential detection points: if Task A’s role is suddenly used to perform actions it normally never does (especially outside the expected context or time window for Task A), that’s a red flag. Importantly, merely receiving the credential payloads over ACS does not produce any CloudTrail events – it’s an internal push from AWS to the agent.

A few limitations/nuances to note: If a task on the instance has no task role defined, naturally there are no credentials to steal from it. Tasks that start after our session is established will also have their credentials sent over ACS (and we’ll capture those too, as long as our rogue WebSocket remains connected). We also receive any execution role credentials in the ACS stream (for tasks that use a separate execution role for pulling images, etc.), although those typically grant limited permissions (like access to ECR, CloudWatch Logs, or Secrets Manager for that task’s operations) – still, in some cases these could be leveraged in an attack or chained with other credentials.

In summary, ECS centralizes the AssumeRole process in the control plane and then “moves” those ephemeral credentials to the on-host agent, relying on the secrecy of that ACS channel and per-task metadata scoping for isolation. By impersonating the agent’s upstream connection, ECScape completely collapses that trust model: one compromised container can passively collect every other task’s IAM role credentials on the same EC2 instance and immediately act with those privileges.

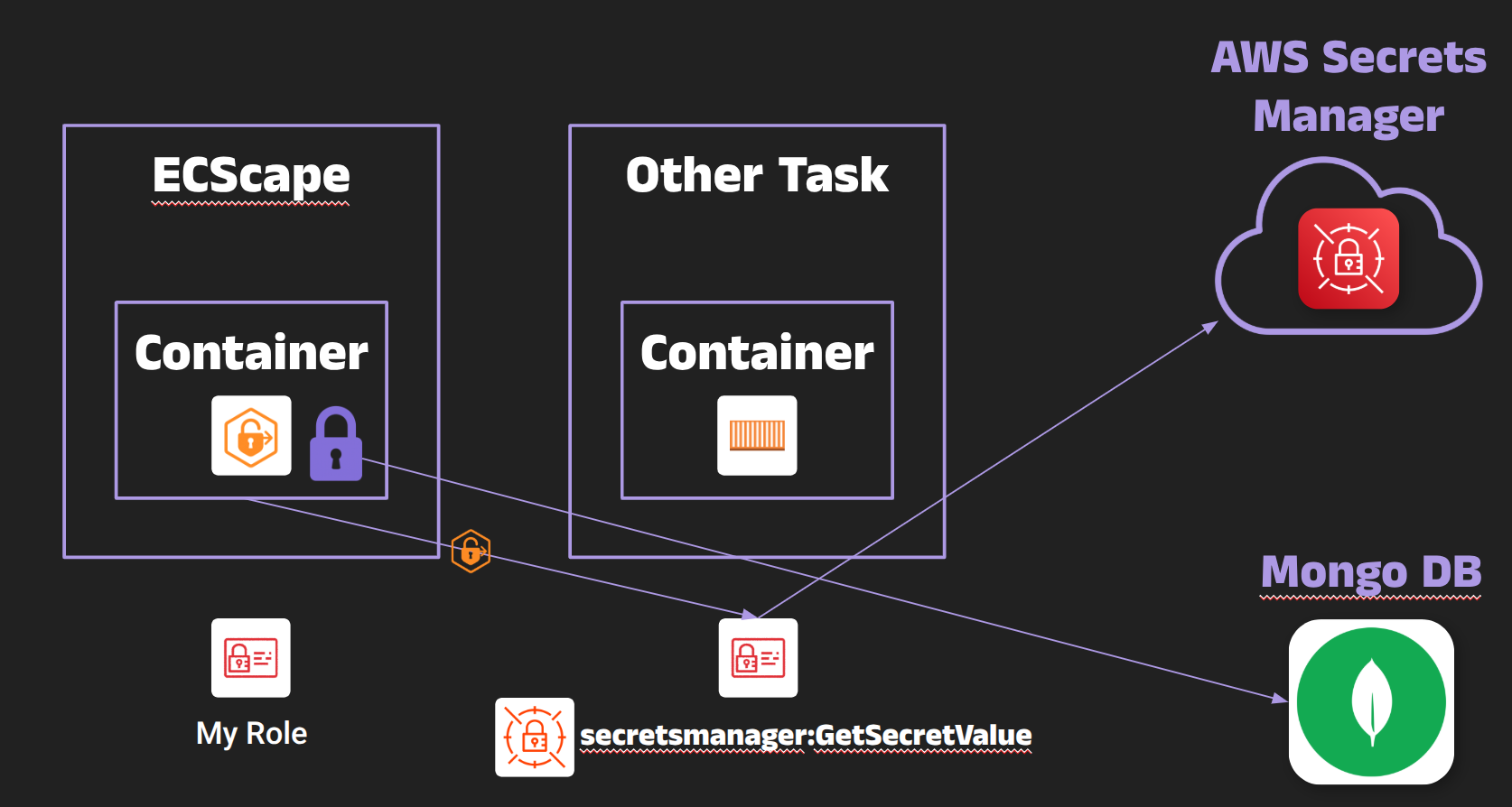

Impact: Why ECScape Is So Severe

The implications of ECScape are far-reaching for anyone running ECS tasks on shared EC2 hosts:

Cross-Task Privilege Escalation: A fundamental promise of containerized workloads is that one compromised application remains isolated from others. ECScape shatters that assumption for ECS on EC2. A low-privileged task can become a high-privileged one by simply stealing its IAM credentials. In effect, any task can impersonate any other task on the same host, permission‑wise. This breaks multi-tenancy and defense-in-depth boundaries. For example, imagine a security scanning container (with only read-only access to a few resources) running alongside a database backup container (with full database and S3 backup access). If the scanner container is compromised, it could use ECScape to grab the backup container’s IAM role and thereby gain direct access to the database or backups, completely undermining the isolation you expected.

Host Role Impersonation: By stealing the ecsInstanceRole credentials from IMDS in Step 1, an attacker can also impersonate the ECS container instance itself when talking to the ECS control plane. This means they could potentially register fake tasks, issue commands to stop or start tasks (effectively causing Denial of Service or rogue deployments), or even register new container instances into the cluster. Essentially, they can pretend to be the ECS agent managing that instance. For example, the attacker could use the instance role to drain all tasks on the host (stop them). Since the instance role often has permissions to update the ECS agent status and respond to ACS directives, the attacker has considerable power over the cluster’s state.

Metadata Exfiltration & Reconnaissance: Impersonating the agent yields more than just credentials. The ACS stream also carries rich task metadata about the environment, which an attacker can collect for reconnaissance. This includes things like full lists of running Task ARNs and their task definition revisions, container image IDs and digests, each task’s CPU and memory configuration, network details (ENI IDs, IP addresses), and the container instance’s own attributes (AMI ID, Availability Zone, etc.). This information can help the attacker map out what’s running on the host and identify high-value targets.

Stealth and Lack of Immediate Detection: The actions taken in ECScape are surprisingly stealthy. Everything the attacker does can look like normal operations from AWS’s perspective:

The calls to ecs:Poll and related APIs used to establish the channel are typical for an ECS agent (though an additional connection from the same instance might be an anomaly, it’s not noisy in itself).

Using stolen credentials to access AWS resources will appear as the legitimate task roles doing so. CloudTrail logs will show the role (and the task ARN session context) performing actions, not an obvious “someone else”. There’s no inherent indicator that the credentials were stolen, without correlation to the task’s expected behavior. If the attacker is careful – for instance, only using the credentials in ways that align with that role’s normal activities (reading data the role usually reads, or performing actions during times that don’t stand out) – it might not raise immediate flags.

CloudTrail and Audit Artifacts: There is one silver lining: because each set of task credentials is tied to a task ARN, any use of those credentials in AWS is attributed to that task’s role. So if Task A’s credentials are used to do something that Task A never normally does (especially at an odd time or from a different environment), an investigation will reveal “Task A’s role did X at time Y,” which is suspicious if Task A wasn’t actually doing that. AWS documentation notes that CloudTrail will show which task’s role was used for a given API call. In an ECScape scenario, you’d eventually see, for example, that Task B’s role performed some admin action at a time Task B wasn’t running or was idle – a clue that Task B’s credentials were misused. This can aid incident response (though it’s after-the-fact).

No Misconfiguration Required: Perhaps the scariest part of ECScape is that it doesn’t rely on any obvious user misconfiguration. All the default behaviors and settings of ECS on EC2 (IMDS enabled, instance role with the default ECS permissions, multiple tasks sharing an EC2 host) are enough for the attack to work. In other words, hundreds of millions of ECS tasks running under default conditions were hypothetically vulnerable. This isn’t a case of “you left something open that you shouldn’t have” – it’s more like a design flaw in how credentials were isolated on shared hosts.

In the live demo of ECScape, I showcased this chaining effect: I started in a task that had an IAM policy of “deny all” (it wasn’t allowed to call any AWS API itself). On the same host, another task had a role with broad administrative permissions. Using ECScape, the low-privileged task grabbed the admin role credentials of the other task, then used those credentials to delete an S3 bucket that only an admin could delete. The takeaway is clear – a breach in one container could directly compromise critical resources across your cloud environment.

Mitigation and Best Practices for ECS

AWS’s official response to this issue was that ECS was operating within its intended design: containers sharing an EC2 host are implicitly in the same trust domain unless you isolate them. In other words, from AWS’s perspective this was “working as designed” (more on their response later), and they did not issue a patch or CVE since they did not view it as a vulnerability in the service. This means it’s on AWS users to harden their ECS-on-EC2 environments. Here are important mitigation steps and best practices to protect against ECScape-like scenarios:

Disable or Limit IMDS Access for Tasks: The instance metadata endpoint is the source of the instance role credentials, which are the first thing an attacker needs. If your containers have no need to query IMDS, you should prevent them from reaching it. AWS provides ways to disable IMDSv1 and require IMDSv2, or even disable IMDS for an instance entirely – but note, you cannot fully disable IMDS on an ECS EC2 host without breaking the ECS agent’s functionality (the agent itself needs IMDS to get credentials). Instead, use network controls to block 169.254.169.254 from within containers. For example, if you use awsvpc network mode, you can apply security groups that deny egress to the IMDS IP for the task ENIs. In bridge network mode, you might use iptables rules on the host or the ECS agent’s ECS_AWSVPC_BLOCK_IMDS setting for specific tasks. This is the single most effective mitigation: if a container can’t access IMDS, it can’t steal the instance credentials needed to impersonate the agent.

Restrict ECS Agent Permissions (ecs:Poll): The instance IAM role must have ecs:Poll for the ECS agent to do its job, so you cannot remove it entirely. However, be careful not to grant ecs:Poll or ecs:DiscoverPollEndpoint to any task roles. In normal setups you wouldn’t, but if someone crafted overly broad IAM policies (e.g. an IAM role with ecs:* actions for a task), that task could potentially initiate the exploit on its own without even needing the instance credentials. So ensure no task role has the ability to call ECS control plane APIs that the agent uses.

Isolate High-Privilege Tasks: Whenever possible, do not co-locate highly sensitive or high-privilege tasks on the same EC2 instances as untrusted or low-privilege tasks. If you have a task with an admin role or access to very sensitive data, run it on a separate EC2 instance (or a separate cluster) from your less privileged workloads. Essentially, treat each EC2 host as a failure domain – tasks sharing a host should have similar trust and privilege levels. This might mean using dedicated capacity (or separate ECS clusters) for different sensitivity levels of tasks.

Use AWS Fargate for Stronger Isolation: AWS Fargate tasks don’t share an underlying host with other tasks – each Fargate task runs in its own micro VM with its own isolated IMDS and ECS agent. ECScape does not apply to Fargate because there is no co-tenancy of the instance. If your security requirements are strict, it might be worth the cost to run certain workloads under Fargate for the added isolation. (AWS explicitly recommends Fargate for multi-tenant scenarios to avoid the class of issues exemplified by ECScape.)

Task IAM Least Privilege: Continue to enforce least privilege on all your task IAM roles. While this won’t prevent credential theft, it can limit the blast radius. If Task A doesn’t actually need admin rights, then even if Task B steals Task A’s credentials, Task B won’t gain admin rights. In an ideal setup, even if an attacker compromises one low-privileged task and steals all other tasks’ credentials on the host, none of those credentials are particularly powerful. Segmenting roles and privileges can significantly reduce the value of any one credential compromise.

Monitoring and Detection: Implement monitoring to catch suspicious behavior:

Set up CloudTrail alerts or AWS Config rules to flag unusual usage of IAM roles. For instance, if a certain task’s role is suddenly used to perform AWS actions outside its normal pattern (e.g., at odd hours, from an unusual IP/location if it somehow gets used outside AWS, or calling APIs it normally never calls), investigate it.

AWS GuardDuty has a finding for EC2 instance credentials used from an external IP, which could catch the case where stolen instance credentials are taken outside. It may also flag atypical API patterns; intra-AWS misuse of task credentials is harder, so combine with CloudTrail anomaly alerts.

On the host side, consider monitoring network connections. The ECS agent typically only connects out to specific AWS endpoints. If you detect a container process establishing a WebSocket to an AWS domain that it normally wouldn’t, that’s a red flag. Similarly, any calls to ECS APIs (ecs:Poll etc.) originating from containers should be nonexistent in a normal environment. While challenging, advanced detection could involve a sidecar or eBPF-based watcher looking for usage of the instance role credentials from within containers.

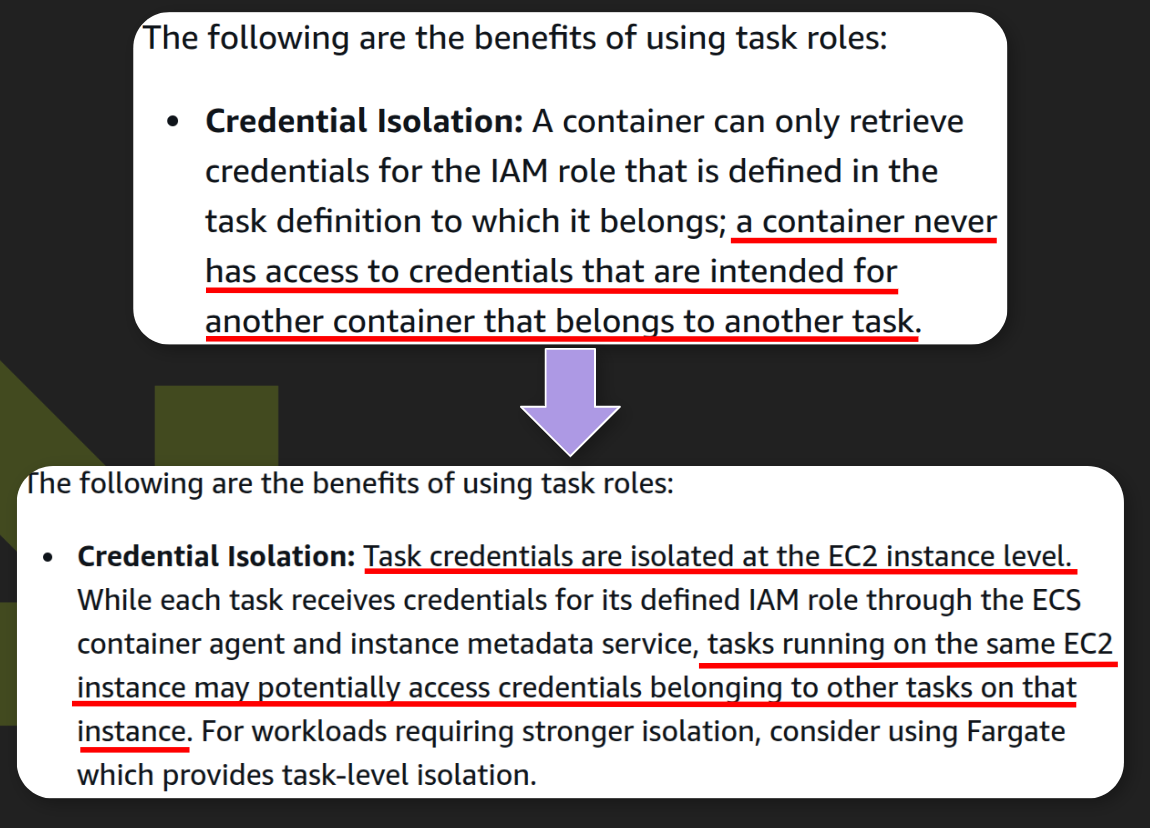

By implementing the above – especially locking down IMDS for tasks – you can significantly reduce the risk of an ECScape-style attack. In fact, AWS’s documentation was updated after this research to explicitly warn that “tasks running on the same EC2 instance may potentially access credentials belonging to other tasks on that instance,” and it strongly encourages using Fargate for stronger isolation and monitoring cross-task role usage via CloudTrail.

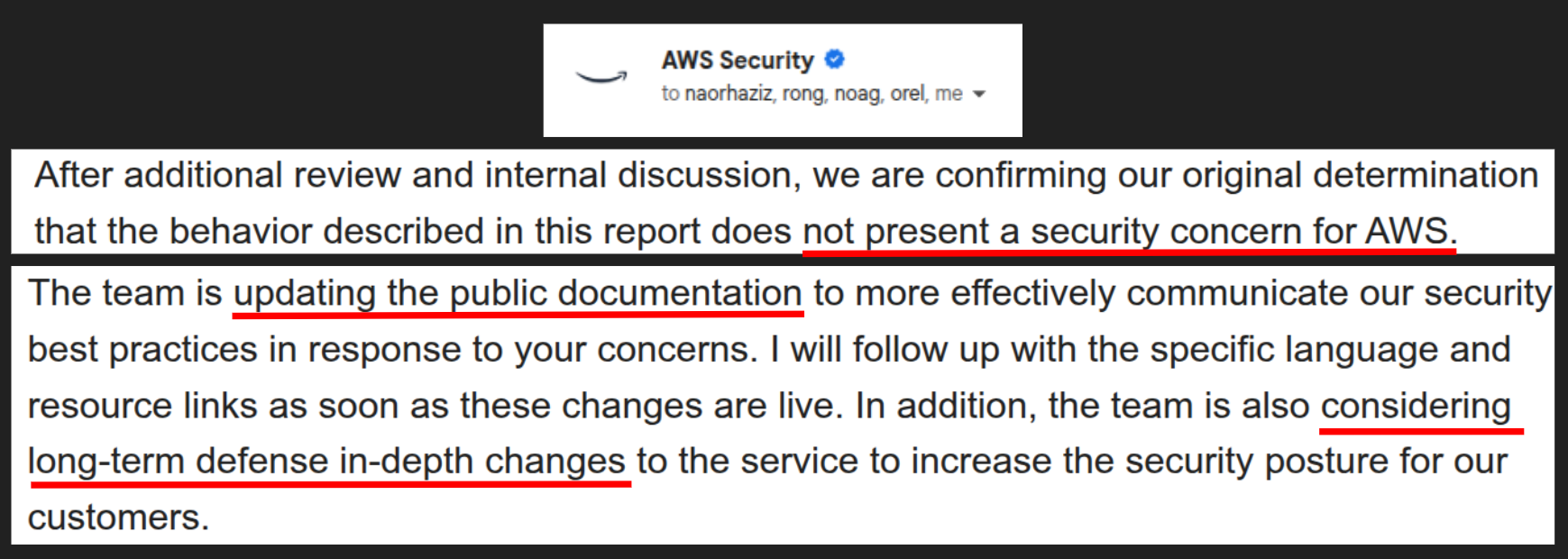

AWS’s Response and Final Thoughts

When we reported ECScape to AWS, they acknowledged the behavior but replied that it “does not present a security concern for AWS” – essentially, they viewed it as working within the intended trust model of ECS on EC2. In AWS’s eyes, containers sharing an EC2 instance are not guaranteed isolation from each other unless the user provides that isolation. They did not issue a CVE or a security bulletin for this, since it wasn’t considered a vulnerability breaking AWS’s security boundaries (from their perspective).

However, AWS did take two noteworthy actions in response:

- Documentation Update: AWS updated their public documentation to make it crystal clear that on ECS with EC2 launch type, one task can potentially access credentials intended for another task on the same host if you (the user) aren’t careful. The docs now explicitly highlight that task credentials are isolated only at the instance level (not absolute per-task isolation) and mention this exact scenario, along with a recommendation to use Fargate for stronger guarantees. They also emphasize auditing of task role usage via CloudTrail as a best practice. This change serves as an official acknowledgement of the risk and guides customers on how to mitigate it.

- Recognition (Non-monetary): While we didn’t receive a bounty (since technically this was “working as designed” and not a bug bounty scope issue), AWS did provide a statement of appreciation. They also indicated they would add public recognition for the research in their documentation change log. In other words, AWS agreed it was important enough to document and credit, even if they didn’t classify it as a vulnerability.

From a researcher’s perspective, ECScape was a deep dive into how ECS stitches together control-plane role assumption, on-host credential delivery, and container isolation. The core lesson is that you should treat each container as potentially compromiseable and rigorously constrain its blast radius. AWS’s convenient abstractions (task roles, metadata service, etc.) make life easier for developers, but when multiple tasks with different privilege levels share an underlying host, their security is only as strong as the mechanisms isolating them – mechanisms which can have subtle weaknesses.

As the industry moves toward stronger isolation models (e.g. AWS Fargate’s per-task microVM, Firecracker, gVisor, and other sandboxing or even hardware-based isolation like Nitro enclaves), this particular class of cross-container credential theft becomes much harder. But today, many environments still run heterogeneous workloads on shared EC2 instances for cost or management reasons. ECScape blurs the line between misconfiguration, design trade-off, and exploit – and it underscores the importance of defense in depth. Things like blocking unnecessary IMDS access, enforcing least privilege, isolating critical tasks, and monitoring for anomalies aren’t just box-checking best practices; they can each break a link in the kill chain we described.

Ultimately, improving security in scenarios like this is a shared responsibility. Cloud providers need to continually refine isolation primitives and credential delivery mechanisms, and cloud users need to architect with the assumption that any one container might become malicious. By understanding exactly how ECS credential delivery works (as we’ve done here) and where the trust boundaries lie, you can make more informed decisions about your cloud architecture and monitoring.

Thanks for reading! Got similar stories or ideas about ECS security? Feel free to reach out :)